Indeed, this strategy is more effective when bravehearts deploy changes with ambition and report real-world problems, as we know that it is difficult to exhaustively test a change to the point of eliminating all possible new defective behaviors.

Post

Indeed, this strategy is more effective when bravehearts deploy changes with ambition and report real-world problems, as we know that it is difficult to exhaustively test a change to the point of eliminating all possible new defective behaviors.

While many things have not changed since this paper was published in 2002, the landscape around #CVE and open source software has, in my opinion.

This paper mainly contemplates official patches and bulletins from commercial vendors, or at least a CVE that was reviewed by a panel of editors. It rightly calls out that the quality of fixes varies widely.

However, today a CVE in a FOSS package may mean little to nothing in context of a production product or system.

#FOSS

@smb @adamshostack

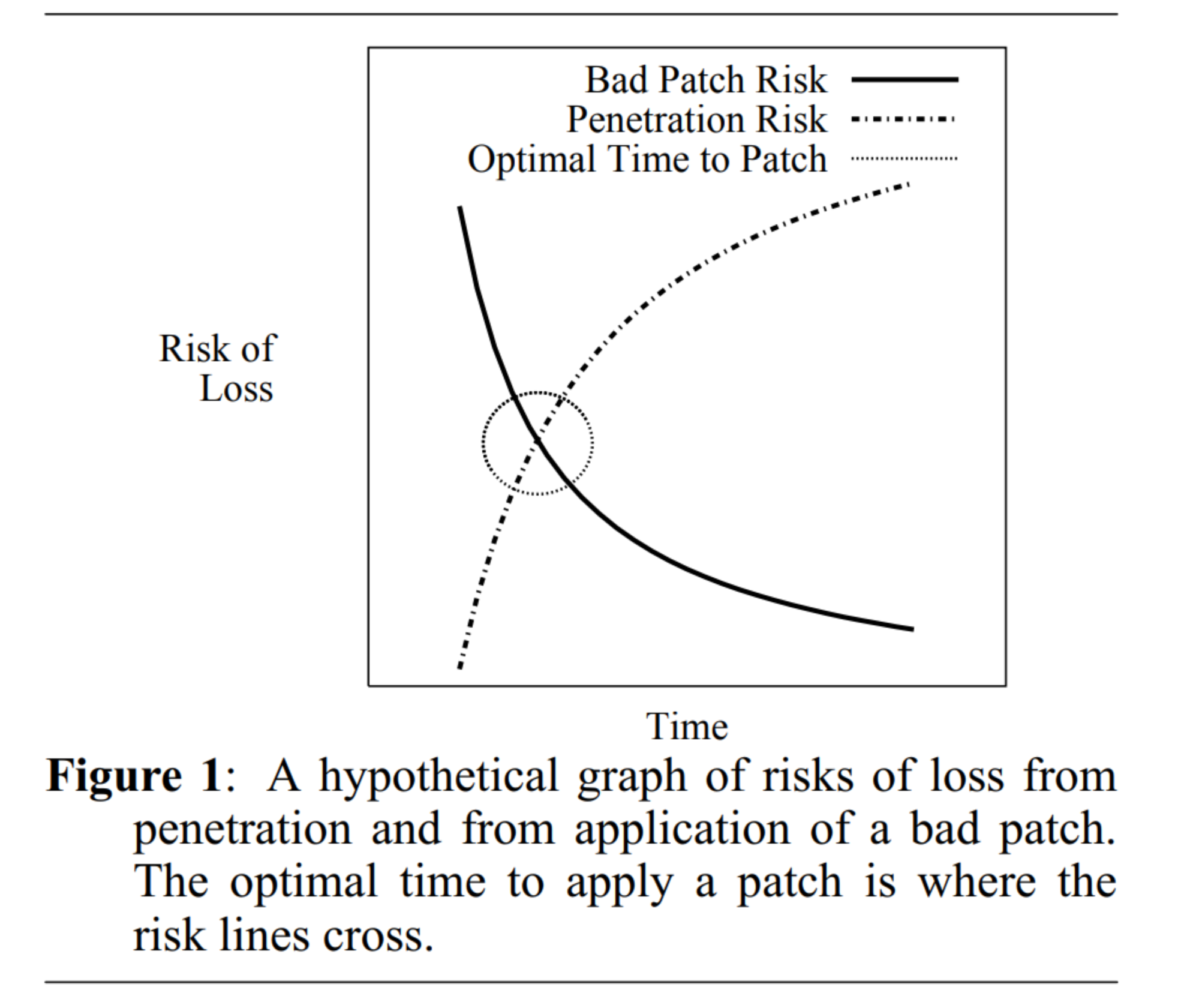

I definitely recommend folks read the paper linked in the first post. Here's a TL;DR summary in the form of Figure 1: " "A hypothetical graph of risks of loss from penetration and from application of a bad patch. The optimal time to apply a patch is where the risk lines cross."

Folks who like that paper may light this one as well.

It studies Microsoft "Patch Tuesday" updates in particular, which are much different (in my opinion) than your typical open source software updates that are labeled with a CVE.

bonfire.cafe

A space for Bonfire maintainers and contributors to communicate