Democratic Socialism as Public Action

Municipal Politics as Praxis

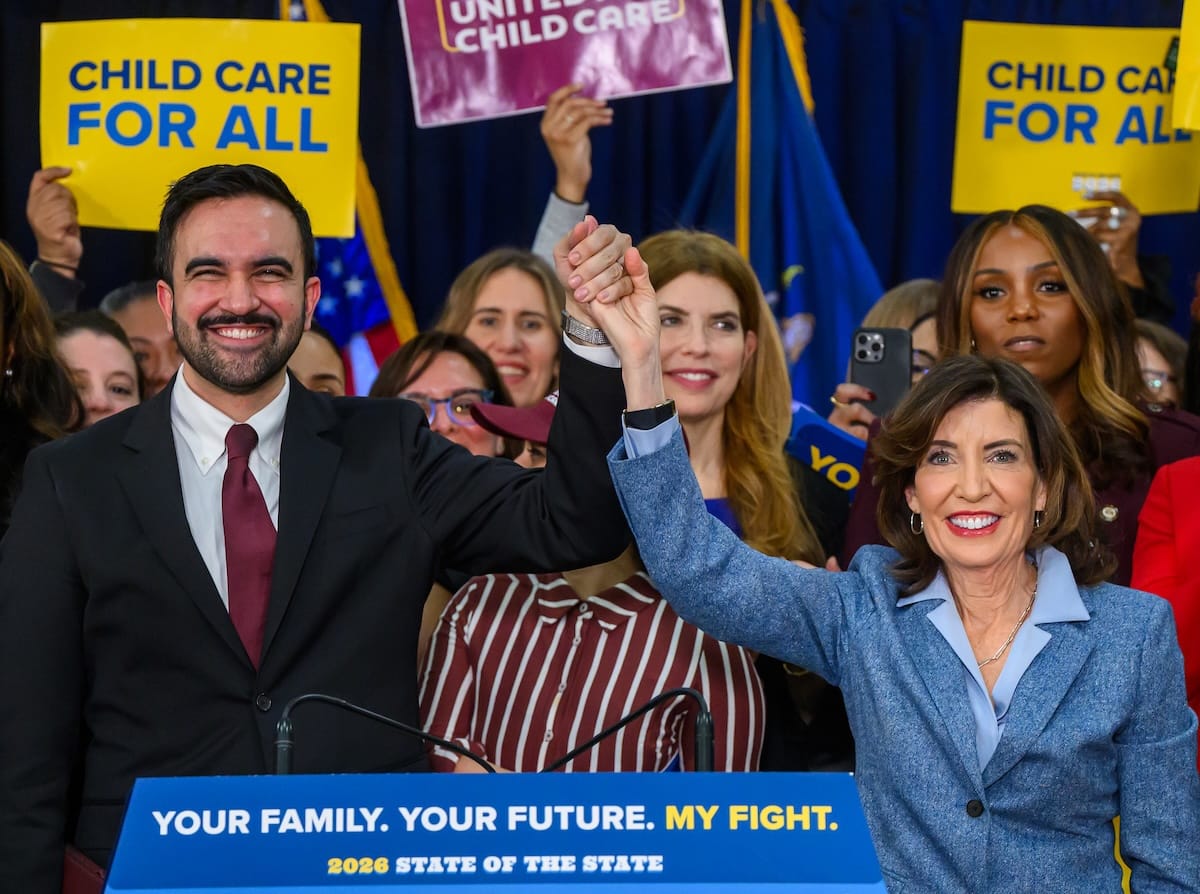

Over the past year, many of us supported Zohran Mamdani because we believed he represented more than a set of policy positions. He seemed to be pointing toward a different way of doing politics—one grounded in participation, visibility, moral clarity, and a refusal to accept the quiet shrinking of public life as inevitable. Now that he is mayor, the question has necessarily changed. The campaign is over. The work of governing has begun. What does democratic socialism look like in practice, once slogans give way to decisions, institutions, and constraints?

That is why this article is worth reading carefully. Not because it praises Mamdani, and not because it claims everything is going smoothly, but because it treats his first weeks in office as a serious political experiment—one with real stakes, real resistance, and real limits. It asks what it means for socialism to become legible as governance, rather than remaining a posture of opposition or a set of ideals waiting for perfect conditions.

One of the most important themes running through the piece is the distinction between policies that merely deliver benefits and politics that actively reshape how people understand their relationship to government and to one another. There is a difference between public goods that are quietly administered and public goods that are openly claimed, explained, and defended as collective achievements. The article suggests—rightly, I think—that socialism succeeds or fails not only on outcomes, but on whether it makes public power visible, accountable, and shared, rather than hidden behind technocratic language or market logic.

The essay also pushes back against two familiar temptations on the left. One is the belief that compromise automatically equals betrayal. The other is the idea that working through institutions is inherently corrupting. What Mamdani’s early moves illustrate is something more demanding: governing as an ongoing process of judgment, direction, and repair. Not purity, but coherence. Not spectacle, but capacity. Not withdrawal from conflict, but a willingness to name what is at stake and act accordingly.

If you are interested in how socialism might be pursued in a way that is serious about power, administration, and democratic legitimacy—without losing its moral imagination—this article repays attention. It does not offer a blueprint. What it offers instead is a way of seeing what is unfolding, and of asking better questions about what must come next.

#MayorMamdani

#UnderstandMamdani

#ZohranMamdani

#EmbodiedPolitics

#ReinventingSocialism

https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/socialism-in-one-city/?utm_source=Boston+Review+Email+Subscribers&utm_campaign=376bd7d215-ourlatest_1_17_26_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_2cb428c5ad-376bd7d215-40979853&mc_cid=376bd7d215